Please look at

http://www.adbusters.org/home/#

Pageviews last month

Monday 21 January 2008

Sunday 20 January 2008

As Shanks says(online, 12-01-08)"The decay of an artifact is a token of the human condition. The fragment, the mutilated and incomplete thing from the past, brings a sense of life struggling with time: death and decay await us all, people and objects alike. In common we have our materiality"

http://documents.stanford.edu/MichaelShanks/229

http://www.julianstair.com/

http://www.edmunddewaal.com/

http://www.marekcecula.com/sites/artist.php

It is the work of artists such as these which has provoked the line of reasoning set out below. I also worked as a field archaeologist for six years in 70’s +80’s. Thus the interdisciplinary approach to the study of ceramics is essential to me.

Colin Renfrew says

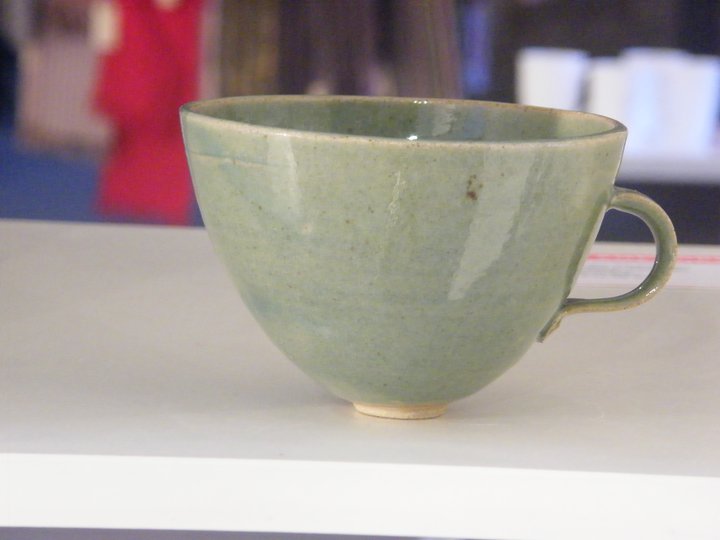

This proposal contains an introduction, the theoretical/conceptual background to the project, aims and intentions, proposed research design and method, which will present research questions for the origins and genesis of the mug/cup - the individual, handled, ceramic drinking vessel. Its history is often associated with the teapot, and although the teapot is often mentioned this is usually used to illuminate a point about the mug/cup when no other reference exists. The focus will always be the cup/mug. (SAY SOMETHING ABOUT LONGEVITY AND CONTINUITY).

Certain key issues in archaeology arise out of this study - the relationship between social practices and material culture; Social changes manifested in material culture; the relationship between the past and the present; the relationship between people and objects

The mug/cup as an everyday object has been made, bought, used and discarded or in some cases collected and curated now for nearly six hundred years- how has this happened? Is there any other object that this has happened to? The book, specifically the English bible, undoubtedly;;, the clay pipe, however, became obsolete. These sorts of questions will need further exploration.

As Michael Shanks(email, 18-01-08) has said, this will be “a genealogy of an everyday item - a pragmatogony".

THEORETICAL/CONCEPTUAL BACKGROUND,

WHAT IS IT I AM TRYING TO FIND OUT?

There is a well documented transition from the medieval to the post medieval period. Indeed Barker,(Accessed on line 30-12-07) attests to a transitional phase defined by transitional groups of pottery. The Post Medieval period, 1450-1700, according to Cumberpatch,(2003), refers more or less to a period which follows the medieval and is largely defined by the material culture of this context. From these contexts come large amounts of ceramic material which are distinctive from the medieval ceramics. They consist of assemblages which have a specific character, are described as transitional groups containing cups platter, jugs, pancheons, dripping pans, as seen in FIG 1. The medieval forms had largely been replaced by vessels with specific functions some of which are still readily recognisable in the contemporary period.

The Early industrial Revolution is the same period but refers to social, technological and economic change of the 15th and 16th century in Great Britain.

Furthermore, the earliest historical reference to an earthenware platter is in 1666, and is of Samuel Pepys dining (Coleman-Smith, 1988, pg 174) “it is unusual to find pottery examples before the post medieval period”.

The teapot arrived into the post-medieval period, 1600-1720 a period which can be seen as the start of the consumer age with ”a wider variety of mass produced forms in varying colours.

FIG 1

Coleman-Smith(1988), and Cumberpatch(2003) provide evidence for the theoretical background. Additionally, Gaimster and Stamper(1997) document the transition period as context to these changes. Coleman-Smith(1988,p 1) says that, at Donyatt in Somerset,

“the end of the medieval tradition as represented by the 16th century phase production was apparently abrupt, with a complete changeover to new forms, different techniques of production and a new emphasis on decoration”.

Indeed, the 17th century transitional phase of production represented an increase in the variety of forms. This tendency/pattern of increasing variety continued well into the 19th century. Another aspect of this variety is that vessels became more and more specialized - this vessel specificity shows that the preparation and serving of food becomes separated, dining, display and entertainment become the new practices.

could be another aspect of this subject that might benefit from further research. 9(Rewrite this) Lack of resources has prevented further research into this aspect.

Cumberpatch, (2003) has defined the scope of the problem

“in highlighting the inadequacies of the existing explanations and to indicate a possible way forward which involves considering the phenomenological change in ceramics as a significant aspect of wider social change. Above all it is clear that a broader approach to ceramics, which situates them within the realm of material culture generally and connects this with larger social structures, is required if the reasons for the changes are to be interpreted and adequately explained“.

As an undergraduate, the interdisciplinary nature of material cultural studies when writing an essay on the evolution of the teapot became significant set within in a socio-economic historical framework, relating design history to social change/cultural evolution. It emerged almost by accident by juxtaposing statements from two different disciplines about the same subject, and surprising things happened about the type of knowledge that could emerge. At a later date , having read Knappett (2005, p2), in his recent book, Thinking Through Material Culture), the idea became more realistic, as he says “…it gradually becomes apparent, in a rather surprising fashion, how readily some areas lend themselves to interbreeding”. Consequently, for my dissertation, which was entitled the Changing Value and Status of Handmade Pottery began to use evidence from archaeology, design history, consumer studies, social theory, social and economic history to map socio-cultural change through the study of the evolution of artifacts. It is therefore important, for this current project, to use evidence from several disciplines - the full history of ceramics has to be an interdisciplinary exercise to develop a more rounded and integrated overview of the development of tableware. Karl Knappett(2005), says that material Cultural Theory, within archaeology is in its infancy, and it has not yet developed sophisticated theoretical models for understanding the role of artifacts in human societies. One of the theoretical problems is that it is almost impossible to create a model when much information about a person’s relationship with an object is missing. This is the problem of prehistory. On the other hand, the study of a contemporary object which is also found within the archaeological record may open up the possibility of creating a model for understanding the significance of our relationship with objects. This is also a key issue in archaeology. This would introduce anthropology into the study, which would provide the tools for studying our social relationships with our material culture. This would not be part of the focus of the current project I am proposing, but it is another area where further research would be possible.

Objects have meaning over and beyond their functional and formal elements. The mug or cup, the individual handled ceramic drinking vessel, is probably one of the most ubiquitous objects in western societies. It is known as an everyday object. But this object has a beginning, there was a time when it didn’t exist. The context of its introduction is where much of its meaning may be revealed. It was introduced into the British Isles circa 1450, but seemingly did not make an appearance in the Southwest until circa 1550. Initially, it was probably quite a rare object but now its distribution can be seen everywhere. Its introduction is most likely associated with the introduction of hot drinks.

The potters in the Southwest, Bristol etc seemed to be making handled cups before imports from the East. The teapot was imported in the 1650’s.

The handled cup became part of the teaset at a later date; the saucer was first introduced circa 1710 onwards to accompany the increasing use of small cups, as Hilary Young at the Victoria and Albert Museum says

“Teabowls and saucers were imported from China from the third quarter of the 17th-century, and were put together as paired sets by India Co and china dealer's warehousemen. Handled cups for coffee and chocolate were made from around 1690, and were equipped with saucers by the 1710s. Handled teacups with matching saucers were a slightly later development”.

Email 09-03-2007. ceramicsandglass@vam.ac.uk

It is the indigenous development of the handled drinking vessel that will concern this paper.

Other studies that are used in historical archaeology are probate inventories of household, where artefacts are analysed within their domestic contexts. These would be consulted, where there are references to cups and mugs.

My work as potter gives me some insight in that I can look at a piece of ceramic and begin to tell an audience about the person who made the sherd of pottery, their level of skill, and I could in some cases with certain assemblages of pottery begin to draw conclusions about the social organization surrounding the making of the pottery, MAYBE THE MARKET IT HAS BEEN MADE FOR DEPENDING ON THE CONTEXT OF THE POTTERY. I was able to gain a bit more insight into the production of the sherds, see below for Ethics of Improvement. This is an interdisciplinary exercise.

http://www.edmunddewaal.com/

http://www.marekcecula.com/sites/artist.php

It is the work of artists such as these which has provoked the line of reasoning set out below. I also worked as a field archaeologist for six years in 70’s +80’s. Thus the interdisciplinary approach to the study of ceramics is essential to me.

Colin Renfrew says

This proposal contains an introduction, the theoretical/conceptual background to the project, aims and intentions, proposed research design and method, which will present research questions for the origins and genesis of the mug/cup - the individual, handled, ceramic drinking vessel. Its history is often associated with the teapot, and although the teapot is often mentioned this is usually used to illuminate a point about the mug/cup when no other reference exists. The focus will always be the cup/mug. (SAY SOMETHING ABOUT LONGEVITY AND CONTINUITY).

Certain key issues in archaeology arise out of this study - the relationship between social practices and material culture; Social changes manifested in material culture; the relationship between the past and the present; the relationship between people and objects

The mug/cup as an everyday object has been made, bought, used and discarded or in some cases collected and curated now for nearly six hundred years- how has this happened? Is there any other object that this has happened to? The book, specifically the English bible, undoubtedly;;, the clay pipe, however, became obsolete. These sorts of questions will need further exploration.

As Michael Shanks(email, 18-01-08) has said, this will be “a genealogy of an everyday item - a pragmatogony".

THEORETICAL/CONCEPTUAL BACKGROUND,

WHAT IS IT I AM TRYING TO FIND OUT?

There is a well documented transition from the medieval to the post medieval period. Indeed Barker,(Accessed on line 30-12-07) attests to a transitional phase defined by transitional groups of pottery. The Post Medieval period, 1450-1700, according to Cumberpatch,(2003), refers more or less to a period which follows the medieval and is largely defined by the material culture of this context. From these contexts come large amounts of ceramic material which are distinctive from the medieval ceramics. They consist of assemblages which have a specific character, are described as transitional groups containing cups platter, jugs, pancheons, dripping pans, as seen in FIG 1. The medieval forms had largely been replaced by vessels with specific functions some of which are still readily recognisable in the contemporary period.

The Early industrial Revolution is the same period but refers to social, technological and economic change of the 15th and 16th century in Great Britain.

Furthermore, the earliest historical reference to an earthenware platter is in 1666, and is of Samuel Pepys dining (Coleman-Smith, 1988, pg 174) “it is unusual to find pottery examples before the post medieval period”.

The teapot arrived into the post-medieval period, 1600-1720 a period which can be seen as the start of the consumer age with ”a wider variety of mass produced forms in varying colours.

FIG 1

Coleman-Smith(1988), and Cumberpatch(2003) provide evidence for the theoretical background. Additionally, Gaimster and Stamper(1997) document the transition period as context to these changes. Coleman-Smith(1988,p 1) says that, at Donyatt in Somerset,

“the end of the medieval tradition as represented by the 16th century phase production was apparently abrupt, with a complete changeover to new forms, different techniques of production and a new emphasis on decoration”.

Indeed, the 17th century transitional phase of production represented an increase in the variety of forms. This tendency/pattern of increasing variety continued well into the 19th century. Another aspect of this variety is that vessels became more and more specialized - this vessel specificity shows that the preparation and serving of food becomes separated, dining, display and entertainment become the new practices.

could be another aspect of this subject that might benefit from further research. 9(Rewrite this) Lack of resources has prevented further research into this aspect.

Cumberpatch, (2003) has defined the scope of the problem

“in highlighting the inadequacies of the existing explanations and to indicate a possible way forward which involves considering the phenomenological change in ceramics as a significant aspect of wider social change. Above all it is clear that a broader approach to ceramics, which situates them within the realm of material culture generally and connects this with larger social structures, is required if the reasons for the changes are to be interpreted and adequately explained“.

As an undergraduate, the interdisciplinary nature of material cultural studies when writing an essay on the evolution of the teapot became significant set within in a socio-economic historical framework, relating design history to social change/cultural evolution. It emerged almost by accident by juxtaposing statements from two different disciplines about the same subject, and surprising things happened about the type of knowledge that could emerge. At a later date , having read Knappett (2005, p2), in his recent book, Thinking Through Material Culture), the idea became more realistic, as he says “…it gradually becomes apparent, in a rather surprising fashion, how readily some areas lend themselves to interbreeding”. Consequently, for my dissertation, which was entitled the Changing Value and Status of Handmade Pottery began to use evidence from archaeology, design history, consumer studies, social theory, social and economic history to map socio-cultural change through the study of the evolution of artifacts. It is therefore important, for this current project, to use evidence from several disciplines - the full history of ceramics has to be an interdisciplinary exercise to develop a more rounded and integrated overview of the development of tableware. Karl Knappett(2005), says that material Cultural Theory, within archaeology is in its infancy, and it has not yet developed sophisticated theoretical models for understanding the role of artifacts in human societies. One of the theoretical problems is that it is almost impossible to create a model when much information about a person’s relationship with an object is missing. This is the problem of prehistory. On the other hand, the study of a contemporary object which is also found within the archaeological record may open up the possibility of creating a model for understanding the significance of our relationship with objects. This is also a key issue in archaeology. This would introduce anthropology into the study, which would provide the tools for studying our social relationships with our material culture. This would not be part of the focus of the current project I am proposing, but it is another area where further research would be possible.

Objects have meaning over and beyond their functional and formal elements. The mug or cup, the individual handled ceramic drinking vessel, is probably one of the most ubiquitous objects in western societies. It is known as an everyday object. But this object has a beginning, there was a time when it didn’t exist. The context of its introduction is where much of its meaning may be revealed. It was introduced into the British Isles circa 1450, but seemingly did not make an appearance in the Southwest until circa 1550. Initially, it was probably quite a rare object but now its distribution can be seen everywhere. Its introduction is most likely associated with the introduction of hot drinks.

The potters in the Southwest, Bristol etc seemed to be making handled cups before imports from the East. The teapot was imported in the 1650’s.

The handled cup became part of the teaset at a later date; the saucer was first introduced circa 1710 onwards to accompany the increasing use of small cups, as Hilary Young at the Victoria and Albert Museum says

“Teabowls and saucers were imported from China from the third quarter of the 17th-century, and were put together as paired sets by India Co and china dealer's warehousemen. Handled cups for coffee and chocolate were made from around 1690, and were equipped with saucers by the 1710s. Handled teacups with matching saucers were a slightly later development”.

Email 09-03-2007. ceramicsandglass@vam.ac.uk

It is the indigenous development of the handled drinking vessel that will concern this paper.

Other studies that are used in historical archaeology are probate inventories of household, where artefacts are analysed within their domestic contexts. These would be consulted, where there are references to cups and mugs.

My work as potter gives me some insight in that I can look at a piece of ceramic and begin to tell an audience about the person who made the sherd of pottery, their level of skill, and I could in some cases with certain assemblages of pottery begin to draw conclusions about the social organization surrounding the making of the pottery, MAYBE THE MARKET IT HAS BEEN MADE FOR DEPENDING ON THE CONTEXT OF THE POTTERY. I was able to gain a bit more insight into the production of the sherds, see below for Ethics of Improvement. This is an interdisciplinary exercise.

Saturday 19 January 2008

BIBLIOGRAPHY

*Allan, J. (1984) Medieval and Post-Medieval Finds from Exeter Exeter Museum

Allan, J and Barber, J. 1992. A seventeenth-century pottery group from the Kitto Institute , Plymouth. In Gaimster, D and Redknap, M (eds), Everyday and Exotic Pottery from Western Europe: Studies in honour of J.G.Hurst, 225_245. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Allan, J, (1994) Imported Pottery in South-West England, c. 1350-1550. Medieval Ceramics 18:45-50.

Allan, J. 1999. Producers, distributors and redistributors: the role of the south western ports in the seventeeth century ceramics trades. In Egan and Michael 1999, 278-288.

Allan, J P. 2003. Patterns of artefact consumption and household usage in the ports of south-west England, ca 1600-1700. In Roy, C, Bélisle, J, Bernier, M-A and Loewen, B (eds), Mer et Monde: Questions d'Archéologie Maritime. Collection Hors-Série, No. 1, 134-149. Association des Archéologues du Québec.

*Appadurai, A., (Ed) (1986). The Social Life of things; Commodities in cultural perspective. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

*Appignanesi, R and Garratt, C.(1999) Introducing Postmodernism. Icon Books. Cambridge.

Arnold, D.E. 1985 Ceramic Theory and Cultural Process. Cambridge University Press.

*Barker, D. Ceramic Industries

http://www.arch-ant.bham.ac.uk/research/fieldwork_research_themes/projects/wmrrfa/seminar6/David%20Barker.doc

Baudrillard, Jean. (Trans. Benedict, J.) (1996) The System of Objects. Verso. London.

Bennett, H.S. 1922 [1990]. The Pastons and their England; Studies in an age of transition. Canto / Cambridge University Press

Berg, M. and Clifford, H. 1999. Consumers and luxury; consumer culture in Europe 1650 – 1850. Manchester University Press

Bermingham, A. and Brewer, J. 1995. The consumption of culture 1600 – 1800: Image, object, text. Rouledge.

Berthoud, Michael: An Anthology of British Cups , Wingham, 1982.

*Britnell, R.H. 1997. The closing of the Middle Ages? England 1471 – 1529 Blackwell

*Buchli, V. ed. 2002. The Material Culture Reader. Oxford: Berg.

Carver, M.O.H. 1985 Theory and practice in urban pottery seriation. J. Archaeological Science 12: 353-366.

*Clark, Garth (1996) The Potter’s Art. New York, Phaidon,

*Clark, Garth. (2004) The Artful Teapot, Thames and Hudson, London.

Chapman, J. 2000. Fragmentation in Archaeology: People, Places and Broken Objects

in the Prehistory of South Eastern Europe. London: Routledge.

Cole, M. 1996. Cultural Psychology: A Once and Future Discipline. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

*Coleman-Smith,R. and Pearson, T.(1988) Excavations in The Donyatt Pottery. Oxford, Philimoore.

Archaeology of Industrialization, The

David Barker and David Cranstone( 2004),

R.H. Britnell (Editor) 1997

The Commercialisation of English Society, 1000-1500 Manchester University Press (Manchester Medieval Studies)

Peter B: In Praise of Hot Liquors, The Study of Chocolate, Coffee and Tea-Drinking 1600-1850, (exhibition held at Fairfax House, York), York, 1995.

*Cumberpatch, C. G. (2003)The Transformation of Tradition: the Origins of the Post-Medieval Ceramic Tradition in Yorkshire,

www.shef.ac.uk/assem/issue7/cumberpatch.html

Dawson. D, and Bone, M,. (2004). Post-Medieval, Industrial and Modern Theme. South West Archaeological Research Framework. Post-Medieval Theme.Resource Assessment: Post-Medieval, Industrial and Modern. http://www.somerset.gov.uk/media/933/63/pm_mod.pdf

Accessed on line 0-05-07

*Del Vecchio, Mark. (2001)Postmodern Ceramics, Thames and Hudson, London.

Mary Douglas, Baron Isherwood(1996). World of Goods. Towards an Anthropology of Consumption. Routledge,an imprint of Taylor & Francis Books Ltd;

Material Culture in London in an Age of Transition: Tudor and Stuart Period Finds C.1450-c.1700 from Excavations at Riverside Sites in Southwark (MoLAS Monograph) (Paperback) by Geoff Egan (Author)

The Civilizing Process (Paperback) by Norbert Elias (Author) "1. The concept of "civilization" refers to a wide variety of

Publisher: Blackwell Publishers; 2Rev Ed edition (May 2000) Language English ISBN-10: 0631221611

Elliott G,(1999). John and David Elers and Their Contemporaries Jonathan Horne (1 Jan)

Aspects of Ceramic History: A Series of Papers Focusing on the Ceramic Artifact as Evidence of Cultural and Technical Developments: v. 1 (Spiral-bound) by Gordon Elliott

Emmerson, Robin: British Teapots and Tea Drinking, London, 1992,

Faulkner, Rupert Ed.: Tea East and West, London, 2003,

Forty, A. and Küchler, S. (eds.), (1999) The Art of Forgetting. Berg: Oxford.

Gaimster and P. Stamper (Eds.) 1997 The age of transition; the archaeology of English culture 1400 – 1600. Oxbow Monograph 98.

Gardner, A. (ed), 2004. Agency Uncovered: Archaeological Perspectives on Social Agency, Power and Being Human. London: UCL Press.

*Gaskell-Brown, Cynthia (ed).(1979) Castle Street: The Pottery, Plymouth Museum Archaeological Series, Number 1. Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery, Plymouth.

Glennie, P. 1995. Consumption within historical studies. In: D. Miller (Ed.) Acknowledging consumption: 164 - 203. Routledge.

Grant, Allison 1983 North Devon Pottery: The Seventeenth Century. The University of Exeter, Exeter, England

Hayfield, C. 1988. The popularity of medieval vessel forms in Humberside. Medieval Ceramics 12:57-68.

Helms, M. 1993. Craft and the Kingly Ideal. Austin: University of Texas Press.

*Holtorf, C. 2002. “Notes on the Life History of a Pot Sherd,” Journal of Material Culture 7(1), 49-71.

*Hoskins, J. 1998. Biographical Objects: How Things Tell the Stories of People’s Lives. London: Routledge.

*Jameson, F.(1991) Postmodernism or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. London. New York, Verso

Jenner, Anne; Vince, Alan G., A late medieval Hertfordshire glazed ware In Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, A dated type-series of London medieval pottery 3(1983). Volume 34 Pages: 151-169 (Object details: p 157 fig 3, paralleled)

Johan Huizinga (1919), The Waning of the Middle Ages (Paperback) New York, Dover Ingold, T. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge.

Robert E. Kleine III, Susan Schultz-Kleine, Jerome B. Kernan, 1992 MUNDANE EVERYDAY CONSUMPTION AND THE SELF: A CONCEPTUAL ORIENTATION AND PROSPECTS for

CONSUMER RESEARCH. Advances in Consumer Research Volume 19,

http://www.gentleye.com/research/cb/acr/acr1992.html

Alfred Gell 1996, Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory

(Paperback)

*Johnson, M. 1996. An archaeology of capitalism Blackwell.

Jones, S. 1997. The Archaeology of Ethnicity. Constructing Identities in the Past and Present. London: Routledge.

Kent, O. 2005. Pots in Use: Ceramics, Behaviour and Change in the Early Modern Period, 1580 -1700. Unpublished PhD thesis, Staffordshire University.

*Knappett, C. 2005. Thinking Through Material Culture: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Philadelphia: Penn Press.

Elizabeth Kowaleski-Wallace1997 Consuming subjects : women, shopping, and business in the eighteenth century. New York : Columbia University Press

*Leach, Bernard.(1940) A Potters Book. London, Faber and Faber.

Historical Archaeologies of Capitalism (Contributions to Global Historical Archaeology) (Hardcover) by Mark P. Leone (Editor), Parker B. Potter (Editor) "The essays in this book are adapted from presentations delivered in 1993 at a School of American Research Advanced Seminar in Santa Fe, New Mexico..." (more)

in the Social Sciences. London: Routledge.

Leeuw, S. van der and Pritchard, A.C. 1984 The Many Dimensions of Pottery. Amsterdam University Press.

Historical Archaeologies of Capitalism (Contributions to Global Historical Archaeology) (Hardcover) by Mark P. Leone (Editor), Parker B. Potter (Editor) "The essays in this book are adapted from presentations delivered in 1993 at a School of American Research Advanced Seminar in Santa Fe, New Mexico..." (more)

Lemonnier, P. 1986. ‘The study of material culture today: toward an anthropology of technical systems’, Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 5, 147-86.

Lemonnier, P. (ed) 1993. Technological Choices: Transformations in Material Cultures Since the Neolithic. London: Routledge.

*McCracken, G.(1990) Culture and Consumption. New Approaches to the Symbolic Character of Consumer Goods and Activities.

Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana Univer0sity press.

Miller, D. 1985. Artefacts as categories. Cambridge: CUP.

Miller, D., ed. 1998. Material Cultures: Why Some Things Matter. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Visual Culture Reader by Nicholas Mirzoeff (2002) "DURING THE FIRST DAYS of the NATO attack on Serbia in April 1999,

Pfaffenberger, B. 1992. “Social anthropology of technology,” Annual Review of

Anthropology 21, 491-516.

Pearce, Jacqueline E.; Lakin, David; Edwards, J.E.C., Border wares Post-medieval pottery in London, 1500-1700: 1 London: HMSO, (1992). Volume 1 Pages: xii, 137 pISSN ISBN 0112904947 (Object details: pl 11, published

*Pearson, T.(1979) ED. Gaskel-Brown, C. Castle Street, the Pottery,Plymouth Excvations. Plymouth City Museum.

*Petroski, H. (1994). The Evolution of Useful Things. New York: Vintage Books.

*Pevsner, Nicholas. (1960) Pioneers of Modern Design. From William Morris to Walter Gropius. Penguin, London.

*Renfrew, C. 2003. Figuring It Out: The Parallel Visions of Artists and Archaeologists. London: Thames and Hudson.

Renfrew, C., Gosden, C. and Demarrais, E. (eds.) in press. Rethinking Materiality: The Engagement of Mind with the Material World. Cambridge: McDonald Institute Monographs.

Roux V. 1989 The Potter's Wheel: Craft Specialisation and Technical Competence New Delhi: Oxford & IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd.

Rice, P. 1987 Pottery Analysis. Chicago University Press.

World Archaeology 15 (3) ceramics

Shanks, M. and Tilley, C.(1992). Reconstructing Archaeology, Theory and Practice. London, Routledge.

Social Theory and Archaeology (Paperback) by Michael Shanks (Author), Christopher Tilley (Author)

Table Settings: The Material Culture and Social Context of Dining, AD 1700-1900 (Hardcover) by James Symonds (Editor) Email: j.symonds@sheffield.ac.uk

Tarlow, S. (2007)The Archaeology of Improvement in Britain, 1750–1850

Cambridge Studies in Archaeology(abstract on line accessed 16-12-07

http://www.cambridge.org/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521864190&ss=exc

Tilley, C. (1999). Metaphor and Material Culture. Blackwell: Oxford.

*Visser, M. (1991) The Rituals of Dinner: The Origins, Evolution, Eccentricities and meaning of Table Manners. London, Penguin.

Wenger, E. 2000. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: CUP

Wertsch, J.V. 1998a. Mind as Action. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williams, E. and Costall, A. 2000. ‘Taking things more seriously: psychological theories of autism and the material-social divide,’ in P.M. Graves-Brown (ed), Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture. London: Routledge, 97-111.

WEBOGRAPHY

http://potweb.ashmolean.org/PotChron6-38.html

http://potweb.ashmolean.org/PotChron6a.html

Medieval Pottery research GROUP bibliography

http://ntserver002.liv.ac.uk/mprg/frame.htm

www.museumoflondon.org.uk

www.images.vam.ac.uk

http://www.englishceramiccircle.org.uk/bulletin/news/index.htm

Allan, J and Barber, J. 1992. A seventeenth-century pottery group from the Kitto Institute , Plymouth. In Gaimster, D and Redknap, M (eds), Everyday and Exotic Pottery from Western Europe: Studies in honour of J.G.Hurst, 225_245. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Allan, J, (1994) Imported Pottery in South-West England, c. 1350-1550. Medieval Ceramics 18:45-50.

Allan, J. 1999. Producers, distributors and redistributors: the role of the south western ports in the seventeeth century ceramics trades. In Egan and Michael 1999, 278-288.

Allan, J P. 2003. Patterns of artefact consumption and household usage in the ports of south-west England, ca 1600-1700. In Roy, C, Bélisle, J, Bernier, M-A and Loewen, B (eds), Mer et Monde: Questions d'Archéologie Maritime. Collection Hors-Série, No. 1, 134-149. Association des Archéologues du Québec.

*Appadurai, A., (Ed) (1986). The Social Life of things; Commodities in cultural perspective. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

*Appignanesi, R and Garratt, C.(1999) Introducing Postmodernism. Icon Books. Cambridge.

Arnold, D.E. 1985 Ceramic Theory and Cultural Process. Cambridge University Press.

*Barker, D. Ceramic Industries

http://www.arch-ant.bham.ac.uk/research/fieldwork_research_themes/projects/wmrrfa/seminar6/David%20Barker.doc

Baudrillard, Jean. (Trans. Benedict, J.) (1996) The System of Objects. Verso. London.

Bennett, H.S. 1922 [1990]. The Pastons and their England; Studies in an age of transition. Canto / Cambridge University Press

Berg, M. and Clifford, H. 1999. Consumers and luxury; consumer culture in Europe 1650 – 1850. Manchester University Press

Bermingham, A. and Brewer, J. 1995. The consumption of culture 1600 – 1800: Image, object, text. Rouledge.

Berthoud, Michael: An Anthology of British Cups , Wingham, 1982.

*Britnell, R.H. 1997. The closing of the Middle Ages? England 1471 – 1529 Blackwell

*Buchli, V. ed. 2002. The Material Culture Reader. Oxford: Berg.

Carver, M.O.H. 1985 Theory and practice in urban pottery seriation. J. Archaeological Science 12: 353-366.

*Clark, Garth (1996) The Potter’s Art. New York, Phaidon,

*Clark, Garth. (2004) The Artful Teapot, Thames and Hudson, London.

Chapman, J. 2000. Fragmentation in Archaeology: People, Places and Broken Objects

in the Prehistory of South Eastern Europe. London: Routledge.

Cole, M. 1996. Cultural Psychology: A Once and Future Discipline. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

*Coleman-Smith,R. and Pearson, T.(1988) Excavations in The Donyatt Pottery. Oxford, Philimoore.

Archaeology of Industrialization, The

David Barker and David Cranstone( 2004),

R.H. Britnell (Editor) 1997

The Commercialisation of English Society, 1000-1500 Manchester University Press (Manchester Medieval Studies)

Peter B: In Praise of Hot Liquors, The Study of Chocolate, Coffee and Tea-Drinking 1600-1850, (exhibition held at Fairfax House, York), York, 1995.

*Cumberpatch, C. G. (2003)The Transformation of Tradition: the Origins of the Post-Medieval Ceramic Tradition in Yorkshire,

www.shef.ac.uk/assem/issue7/cumberpatch.html

Dawson. D, and Bone, M,. (2004). Post-Medieval, Industrial and Modern Theme. South West Archaeological Research Framework. Post-Medieval Theme.Resource Assessment: Post-Medieval, Industrial and Modern. http://www.somerset.gov.uk/media/933/63/pm_mod.pdf

Accessed on line 0-05-07

*Del Vecchio, Mark. (2001)Postmodern Ceramics, Thames and Hudson, London.

Mary Douglas, Baron Isherwood(1996). World of Goods. Towards an Anthropology of Consumption. Routledge,an imprint of Taylor & Francis Books Ltd;

Material Culture in London in an Age of Transition: Tudor and Stuart Period Finds C.1450-c.1700 from Excavations at Riverside Sites in Southwark (MoLAS Monograph) (Paperback) by Geoff Egan (Author)

The Civilizing Process (Paperback) by Norbert Elias (Author) "1. The concept of "civilization" refers to a wide variety of

Publisher: Blackwell Publishers; 2Rev Ed edition (May 2000) Language English ISBN-10: 0631221611

Elliott G,(1999). John and David Elers and Their Contemporaries Jonathan Horne (1 Jan)

Aspects of Ceramic History: A Series of Papers Focusing on the Ceramic Artifact as Evidence of Cultural and Technical Developments: v. 1 (Spiral-bound) by Gordon Elliott

Emmerson, Robin: British Teapots and Tea Drinking, London, 1992,

Faulkner, Rupert Ed.: Tea East and West, London, 2003,

Forty, A. and Küchler, S. (eds.), (1999) The Art of Forgetting. Berg: Oxford.

Gaimster and P. Stamper (Eds.) 1997 The age of transition; the archaeology of English culture 1400 – 1600. Oxbow Monograph 98.

Gardner, A. (ed), 2004. Agency Uncovered: Archaeological Perspectives on Social Agency, Power and Being Human. London: UCL Press.

*Gaskell-Brown, Cynthia (ed).(1979) Castle Street: The Pottery, Plymouth Museum Archaeological Series, Number 1. Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery, Plymouth.

Glennie, P. 1995. Consumption within historical studies. In: D. Miller (Ed.) Acknowledging consumption: 164 - 203. Routledge.

Grant, Allison 1983 North Devon Pottery: The Seventeenth Century. The University of Exeter, Exeter, England

Hayfield, C. 1988. The popularity of medieval vessel forms in Humberside. Medieval Ceramics 12:57-68.

Helms, M. 1993. Craft and the Kingly Ideal. Austin: University of Texas Press.

*Holtorf, C. 2002. “Notes on the Life History of a Pot Sherd,” Journal of Material Culture 7(1), 49-71.

*Hoskins, J. 1998. Biographical Objects: How Things Tell the Stories of People’s Lives. London: Routledge.

*Jameson, F.(1991) Postmodernism or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. London. New York, Verso

Jenner, Anne; Vince, Alan G., A late medieval Hertfordshire glazed ware In Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, A dated type-series of London medieval pottery 3(1983). Volume 34 Pages: 151-169 (Object details: p 157 fig 3, paralleled)

Johan Huizinga (1919), The Waning of the Middle Ages (Paperback) New York, Dover Ingold, T. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge.

Robert E. Kleine III, Susan Schultz-Kleine, Jerome B. Kernan, 1992 MUNDANE EVERYDAY CONSUMPTION AND THE SELF: A CONCEPTUAL ORIENTATION AND PROSPECTS for

CONSUMER RESEARCH. Advances in Consumer Research Volume 19,

http://www.gentleye.com/research/cb/acr/acr1992.html

Alfred Gell 1996, Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory

(Paperback)

*Johnson, M. 1996. An archaeology of capitalism Blackwell.

Jones, S. 1997. The Archaeology of Ethnicity. Constructing Identities in the Past and Present. London: Routledge.

Kent, O. 2005. Pots in Use: Ceramics, Behaviour and Change in the Early Modern Period, 1580 -1700. Unpublished PhD thesis, Staffordshire University.

*Knappett, C. 2005. Thinking Through Material Culture: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Philadelphia: Penn Press.

Elizabeth Kowaleski-Wallace1997 Consuming subjects : women, shopping, and business in the eighteenth century. New York : Columbia University Press

*Leach, Bernard.(1940) A Potters Book. London, Faber and Faber.

Historical Archaeologies of Capitalism (Contributions to Global Historical Archaeology) (Hardcover) by Mark P. Leone (Editor), Parker B. Potter (Editor) "The essays in this book are adapted from presentations delivered in 1993 at a School of American Research Advanced Seminar in Santa Fe, New Mexico..." (more)

in the Social Sciences. London: Routledge.

Leeuw, S. van der and Pritchard, A.C. 1984 The Many Dimensions of Pottery. Amsterdam University Press.

Historical Archaeologies of Capitalism (Contributions to Global Historical Archaeology) (Hardcover) by Mark P. Leone (Editor), Parker B. Potter (Editor) "The essays in this book are adapted from presentations delivered in 1993 at a School of American Research Advanced Seminar in Santa Fe, New Mexico..." (more)

Lemonnier, P. 1986. ‘The study of material culture today: toward an anthropology of technical systems’, Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 5, 147-86.

Lemonnier, P. (ed) 1993. Technological Choices: Transformations in Material Cultures Since the Neolithic. London: Routledge.

*McCracken, G.(1990) Culture and Consumption. New Approaches to the Symbolic Character of Consumer Goods and Activities.

Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana Univer0sity press.

Miller, D. 1985. Artefacts as categories. Cambridge: CUP.

Miller, D., ed. 1998. Material Cultures: Why Some Things Matter. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Visual Culture Reader by Nicholas Mirzoeff (2002) "DURING THE FIRST DAYS of the NATO attack on Serbia in April 1999,

Pfaffenberger, B. 1992. “Social anthropology of technology,” Annual Review of

Anthropology 21, 491-516.

Pearce, Jacqueline E.; Lakin, David; Edwards, J.E.C., Border wares Post-medieval pottery in London, 1500-1700: 1 London: HMSO, (1992). Volume 1 Pages: xii, 137 pISSN ISBN 0112904947 (Object details: pl 11, published

*Pearson, T.(1979) ED. Gaskel-Brown, C. Castle Street, the Pottery,Plymouth Excvations. Plymouth City Museum.

*Petroski, H. (1994). The Evolution of Useful Things. New York: Vintage Books.

*Pevsner, Nicholas. (1960) Pioneers of Modern Design. From William Morris to Walter Gropius. Penguin, London.

*Renfrew, C. 2003. Figuring It Out: The Parallel Visions of Artists and Archaeologists. London: Thames and Hudson.

Renfrew, C., Gosden, C. and Demarrais, E. (eds.) in press. Rethinking Materiality: The Engagement of Mind with the Material World. Cambridge: McDonald Institute Monographs.

Roux V. 1989 The Potter's Wheel: Craft Specialisation and Technical Competence New Delhi: Oxford & IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd.

Rice, P. 1987 Pottery Analysis. Chicago University Press.

World Archaeology 15 (3) ceramics

Shanks, M. and Tilley, C.(1992). Reconstructing Archaeology, Theory and Practice. London, Routledge.

Social Theory and Archaeology (Paperback) by Michael Shanks (Author), Christopher Tilley (Author)

Table Settings: The Material Culture and Social Context of Dining, AD 1700-1900 (Hardcover) by James Symonds (Editor) Email: j.symonds@sheffield.ac.uk

Tarlow, S. (2007)The Archaeology of Improvement in Britain, 1750–1850

Cambridge Studies in Archaeology(abstract on line accessed 16-12-07

http://www.cambridge.org/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521864190&ss=exc

Tilley, C. (1999). Metaphor and Material Culture. Blackwell: Oxford.

*Visser, M. (1991) The Rituals of Dinner: The Origins, Evolution, Eccentricities and meaning of Table Manners. London, Penguin.

Wenger, E. 2000. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: CUP

Wertsch, J.V. 1998a. Mind as Action. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williams, E. and Costall, A. 2000. ‘Taking things more seriously: psychological theories of autism and the material-social divide,’ in P.M. Graves-Brown (ed), Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture. London: Routledge, 97-111.

WEBOGRAPHY

http://potweb.ashmolean.org/PotChron6-38.html

http://potweb.ashmolean.org/PotChron6a.html

Medieval Pottery research GROUP bibliography

http://ntserver002.liv.ac.uk/mprg/frame.htm

www.museumoflondon.org.uk

www.images.vam.ac.uk

http://www.englishceramiccircle.org.uk/bulletin/news/index.htm

Friday 18 January 2008

LINKS

http://potweb.ashmolean.org/PotChron6-38.html

http://potweb.ashmolean.org/PotChron6a.html

Medieval Pottery research GROUP bibliography

http://ntserver002.liv.ac.uk/mprg/frame.htm

www.museumoflondon.org.uk

www.images.vam.ac.uk

http://www.englishceramiccircle.org.uk/bulletin/news/index.htm

http://documents.stanford.edu/michaelshanks/133

http://www.julianstair.com/

http://www.edmunddewaal.com/

http://www.marekcecula.com/sites/artist.php

http://potweb.ashmolean.org/PotChron6a.html

Medieval Pottery research GROUP bibliography

http://ntserver002.liv.ac.uk/mprg/frame.htm

www.museumoflondon.org.uk

www.images.vam.ac.uk

http://www.englishceramiccircle.org.uk/bulletin/news/index.htm

http://documents.stanford.edu/michaelshanks/133

http://www.julianstair.com/

http://www.edmunddewaal.com/

http://www.marekcecula.com/sites/artist.php

I make tableware on a pottery wheel; I have a small shared studio space in Plymouth. For me there is a huge history behind these everyday objects that I make. I have a lifelong association with them at the very least and they hold a special place in my life. I have used them on a daily basis everyday of my life and as a child played with plastic or miniature ceramic equivalents. However, they also hold a place in the material cultural history of western societies. They tie us to the past whether we are aware of it or not. It is well documented how the teapot was introduced but not the cup/mug, the individual handled ceramic vessel, its origins are less clear, and its introduction does not seem to be a watershed like the teapot. What is an intriguing thought is that there was a time when the mug/cup didn’t exist. It is hard tio imagine a world without them. It must have been very different from our own. Indeed, the Medieval Pottery Research Group(1998) says that “vessels which were designed specifically for drinking are rare before the later medieval period”. Much of the evidence for its introduction is archaeological.

The mug/cup as an everyday object has been made, bought, used and discarded or in some cases collected and curated now for nearly six hundred years- how has this happened? Is there any other object that this has happened to? The book, specifically the English bible, undoubtedly;;, the clay pipe, however, became obsolete. These sorts of questions will need further exploration.

There is a well documented transition from the medieval to the post medieval period. Indeed Barker,(Accessed on line 30-12-07) attests to a transitional phase defined by transitional groups of pottery. The Post Medieval period, 1450-1700, according to Cumberpatch,(2003), refers more or less to a period which follows the medieval and is largely defined by the material culture of this context. From these contexts come large amounts of ceramic material which are distinctive from the medieval ceramics. They consist of assemblages which have a specific character, are described as transitional groups containing cups platter, jugs, pancheons, dripping pans, as seen in FIG 1. The medieval forms had largely been replaced by vessels with specific functions some of which are still readily recognisable in the contemporary period.

The mug/cup as an everyday object has been made, bought, used and discarded or in some cases collected and curated now for nearly six hundred years- how has this happened? Is there any other object that this has happened to? The book, specifically the English bible, undoubtedly;;, the clay pipe, however, became obsolete. These sorts of questions will need further exploration.

There is a well documented transition from the medieval to the post medieval period. Indeed Barker,(Accessed on line 30-12-07) attests to a transitional phase defined by transitional groups of pottery. The Post Medieval period, 1450-1700, according to Cumberpatch,(2003), refers more or less to a period which follows the medieval and is largely defined by the material culture of this context. From these contexts come large amounts of ceramic material which are distinctive from the medieval ceramics. They consist of assemblages which have a specific character, are described as transitional groups containing cups platter, jugs, pancheons, dripping pans, as seen in FIG 1. The medieval forms had largely been replaced by vessels with specific functions some of which are still readily recognisable in the contemporary period.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)